What to eat AUSTRIA 🇦🇹 Wiener schnitzel

Wiener schnitzel is a dish surrounded by myths, lore and competing claims. The most notorious of these revolves around field marshal Joseph Radetzky von Radetz... transporting a variation of cotoletta alla milanese from Lombardy to Vienna in 1857... This fable was ripped to shreds in 2007...

Wiener schnitzel

Published December 8, 2023 · by Amanda Rivkin

Wiener schnitzel is a dish surrounded by myths, lore and competing claims. The most notorious of these revolves around field marshal Joseph Radetzky von Radetz, who legend had it was responsible for transporting a variation of cotoletta alla milanese from Lombardy to Vienna in 1857. The myth at the core of this tall tale alleges that an adjutant to Emperor Franz Joseph I named Count Attems made mention of a veal steak in a margin note whilst commenting on the military situation in Lombardy.

This fable was ripped to shreds in 2007 by the linguist Heinz-Dieter Pohl. He traced the story to an 1869 Italian language cookbook, Guida gastronomica d’Italia, which was translated and published in German in 1871 as Italien tafelt. Pohl alleges that prior to the German edition of the Italian cookbook, the legend of schnitzel as a variation of cotoletta alla milanese was unknown in the German-speaking world. Further, Pohl dug into the imperial archives and found no mentions of a Count Attems, suggesting the adjutant himself may have been an invention.

So where did the Wiener schnitzel come from? Different authors cite different years for the first publication of a recipe for the dish – which by no means is necessarily when the first version of the dish appeared. The earliest of these was located by Pohl, the linguist, in 1719 where a cookbook makes reference to a dish called Backhendl, a chicken schnitzel that remains popular in Austrian cooking.

In 1740, a Viennese cookbook entitled Nutzliches Koch-Buch by Ignanz Garler references a dish of “calf-schnitzel with Parmesan cheese and breadcrumbs,” which brings us closer to the modern-day version with veal. Finally in 1831, Katharina Prato’s popular southern German cookbook mentions a dish called “eingebröselte Kalbsschnitzen,” or “breaded veal cutlets.”

What is clear in the legends and mythmaking surrounding the origins of Wiener schnitzel is that the dish reached acclaim and popularity in the mid-nineteenth century. A 14-year-old Archduke Emperor Franz Joseph I wrote in his diary of travelling “from Gmunden to the plain,” where “the sky cleared up and we arrived in Lambach, in beautiful weather, where we had schnitzels made, which we ate with the greatest appetite.”

Further evidence of schnitzel’s popularity across Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century comes from the English barrister, soldier, journalist and author of 20 books Edward Frederick Knight, better known as E.F. Knight. He writes of ordering a schnitzel in a Rotterdam café in 1867.

Multiple sources point to the schnitzel acquiring its Viennese descriptor, or Wiener in German, in the early twentieth century as a way to market the cuisine of the Austrian capital to the world. In Austria, there is also a national holiday dedicated to the dish, which falls on September 9.

In modern times, Austrian law has grown strict on what can properly be termed Wiener schnitzel, restricting the usage in restaurants and similar establishments to schnitzel made of veal only. Pork is about half the price and also popular in Austrian cooking, but legally it must be referred to as Wiener schnitzel von Schwein (Wiener schnitzel with pork) or Wiener Schnitzel Art (Wiener schnitzel style) less a dining establishment run afoul of the authorities. Rules are rules, after all!

At Figlmüller, a Viennese restaurant that claims to be the home of “the one true Wiener schnitzel,” tourists queue up outside daily to have the city’s most famous variation, if not its finest. Once inside the fourth-generation family-run establishment, they are served by waiters in black tuxedoes. Their schnitzel is made with Viennese Kaiser rolls provided by a specialty bread crumb maker. Sunflower seed oil is used to fry the meat.

Variations of schnitzel have spread with immigration out of the German-speaking world into new worlds around the globe. In America, a variation known as chicken-fried steak was developed in Texas Hill Country, the result of German and Austrian immigrants adapting the dish to local ingredients. In Israel, mid-twentieth century immigrants brought schnitzel with them as well but adapted the dish to use chicken or turkey in deference to kashrut kosher laws. In addition to Austria, schnitzel is also counted among Israel’s national dishes.

Recipe

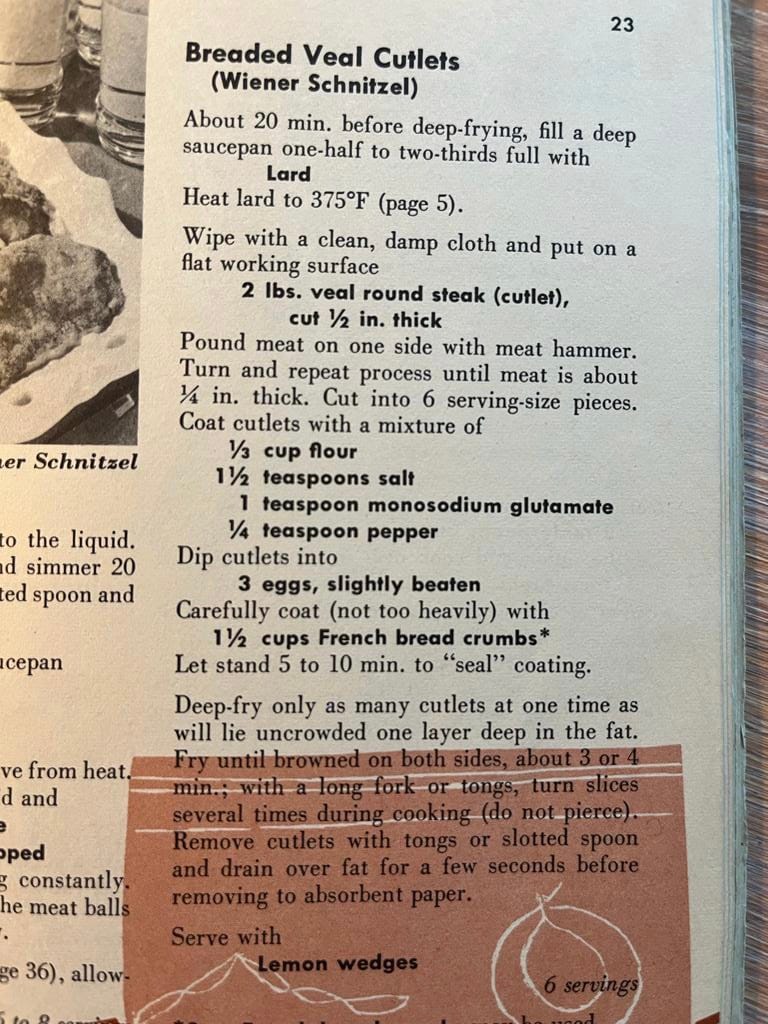

In an effort to show deference to the ancestors as the owner and chef of Restaurant Romy, the Austrian restaurant we visited on this week’s culinary quest, I asked my German-American mother if she had any tips for making schnitzel. She promptly retrieved a fragile copy of her mother’s German and Viennese Cookbook from 1956, the year of the Hungarian Revolution (that other half of the empire that once was).

I adapted and modernized some things. No lard or monosodium glutamate (MSG) is used in my more modern version. Instead, I substitute sunflower seed oil, which Vienna’s most famous establishment for procuring Wiener schnitzel, Figlmüller, does as well. The restaurant is famed for having a line of ready customers each day waiting to taste the finest schnitzel available in the Austrian capital. In lieu of MSG, I used a cajun ingredient, a spice mix known as Tony Cachere’s cajun seasoning, that I bring back from America or have friends and family ferry any time someone crosses the pond.

Ingredients:

A quarter inch steak of veal for each of your guests

400 grams French bread crumbs

400 grams panko bread crumbs

2 tablespoons Tony Cachere’s cajun seasoning (secret ingredient but not necessary)

5 eggs

Sunflower seed oil

Directions:

Step 1: Take each cutlet of veal and the meat hammer and pound on both sides at least twice. Cut larger piece of veal in half. Set on a plate.

Step 2: Make your breadcrumbs! Combine the French bread crumbs and panko bread crumbs. My grandmother’s recipe book calls for adding MSG. Instead, I added a secret ingredient from back home: Tony Cachere’s cajun seasoning.

Step 3: Beat five eggs with a whisk until fluffy. Now dip your veal cutlets into the egg batter and coat both sides in bread crumbs. Set aside for ten minutes so the breading can settle. Do not stack the veal cutlets on top of each other after breading them.

Step 4: Time to fry the schnitzel! Get your oil frying in a schnitzel pan. Make sure there is enough oil to coat both sides of the schnitzel. Place the cutlets in the oil when it is ready. Use a fork and switch on both sides. Place on a tray with a paper towel to absorb excess oil after. Do not stack on top of each other!

Step 5: Serve over a bed of mashed potatoes length-wise across the middle of the plate. Add 3-5 tablespoons of red cabbage or a salad with vinaigrette on one side. You can serve sauteed mushrooms with cream or gravy on top of the mashed potatoes. Then add your Wiener schnitzel on the side of the plate where there is no cabbage or salad, leaned against the bed of mashed potatoes. Enjoy!

Tips, tricks and notes:

The schnitzel must rest ten minutes after it is breaded. This way, you will not lose the breading in the oil.

Learn where to eat Austrian food in Switzerland.

Follow our social media pages @swissglobaldining on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube